Common to all children with reading challenges, is their inability to make reading an automatic process in spite of intensive practice. Researchers have proposed various explanations about the causes of such an inability and, according to current research, dyslexia is due to a weakness of the sound aspect of language; a phonological disability. According to many researchers, nothing can be done about it except to intensify the practice of reading.

Visual challenges in dyslexia

However these modern theories contradict the experience Harald Blomberg of helping many children with reading difficulties to become good readers. Most of these children have been diagnosed as dyslexics. Nevertheless, all of them have suffered from moderate to severe visual challenges. When asked about visual symptoms, they have reported:

- Symptoms such as tiredness, irritation and ocular pain occur

- Headaches while reading

- Text becomes blurry

- Words start to jump or move

- Skip a line or forget which line they’re reading

- Total avoidance of reading

Children with reading difficulties do not spontaneously report their visual challenges and teachers and dyslexia researchers may not ask about them. They have been indoctrinated that dyslexia is exclusively a phonological problem and that it has nothing to do with vision. When never asked about their visual challenges, these children are left to believe that it is absolutely normal that they get a headache, irritation of the eyes or that the text becomes blurry or starts to jump when one reads. Consequently, this leads to feelings that there is something wrong with them because they cannot read like other children.

Development of visual skills.

The development of vision and motor abilities is interrelated. Children develop their vision through the inborn programme of innate baby movements:

- Grasping objects

- Putting them into one’s mouth

- Lifting one’s head in a prone position

- Crawling on one’s stomach

- Getting up on hands and knees

- Rocking and crawling on hands and knees

Children who have motor challenges usually do not make these movements adequately, which ultimately may result in vision challenges.

Primitive reflexes

Primitive reflexes are automatic stereotyped movement patterns outside voluntary control which direct the movements of the fetus and of the infant during the first months of life. Before an infant learns to walk it spends a lot of its time making rhythmic baby movements according to inborn directions. These movements help the infant to integrate its primitive reflexes and the baby must learn to master a considerable amount of movement patterns before it is ready to crawl or walk.

At the age of three years the primitive reflexes should be fully integrated and no longer interfere with movements.

In some children a greater or smaller amount of primitive reflexes remain active, which can be caused by the children having omitted some of these rhythmic baby movements or not having made them sufficiently.

Non integrated primitive reflexes can cause problems with fine and gross motor skill, with vision, and/or articulation and language.

Several primitive reflexes are important for reading and writing, among others the asymmetric tonic neck reflex (ATNR), the symmetric tonic neck reflex (STNR), the Grasp reflex and the Babkin reflex.

Binocular vision and the ATNR

Binocular vision is the ability to direct our eyes to the point we are looking at and to fuse the somewhat different image from each eye into a three dimensional image in the visual cortex.

Binocular vision is dependent on motor development, especially on hand-eye coordination. The most important primitive reflexes for the development of hand-eye coordination and binocular vision are the Asymmetrical Tonic Neck reflex (ATNR) and the Grasp Reflex.

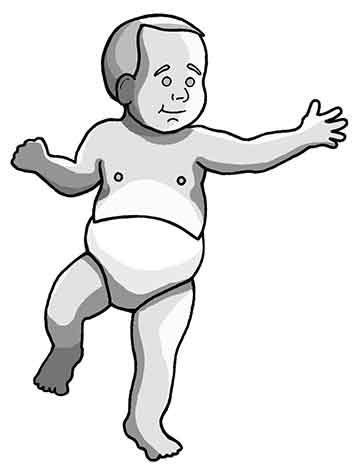

The pattern of the ATNR is that the left arm and leg is stretched when the baby turns his head to the left (see picture). When the baby turns his head to the right, the right arm and leg is stretched and the left bent. The ATNR is integrated after 6-9 months by the child´s grasping things and releasing them and moving them to the other hand. The integration of the ATNR is essential for binocular vision and for the cooperation of the body halves and the hemispheres of the brain.

Some children with severe motor challenges are not able to make such movements and may develop strabismus (wall-eyed or cross-eyed). Strabismus can cause double vision or suspension or suppression of one eye.

Phorias

Some children have so called phorias or ministrabismus a condition in which the direction of one or both of the eyes will change when the eye is covered and relaxes. Unlike people with strabismus, they can still direct both eyes at the same point in space (convergence). They normally have no binocular challenges, like double vision and suspension except when they are tired. These children often need to make an effort to maintain binocular vision when they read, especially in severe phorias.

The following symptoms are typically seen in children with severe phorias:

- Child may have double vision, making the letters run apart or pull together

- Child covers one eye, closes one eye or turns his head to the side to avoid double vision.

- Child may erroneously repeat letters in words when copying a text.

- Child initially reads well, but tires after a while and loses his concentration

- Reading comprehension deteriorates the longer the child reads

- Child is unwilling to read or avoids reading

- Child’s eyes get irritated or hurt after reading for a while.

- Child may develop suppression or suspension of one eye or of both eyes alternately, causing the text to appear to jump.

- Child may get a headache after reading for a while.

Accommodation difficulties

Accommodation is the ability to change focus from a far distance to a short distance and back.

After six months of age, the Symmetric Tonic Neck Reflex (STNR) develops and helps the baby to get up on hands and knees. The integration of this reflex is necessary for good accommodation.

The baby integrates the STNR by rocking on hands and knees looking alternately down into the floor and looking straight out in front of him, focusing out at a distance. This movement will help the baby to develop accommodation.

Nearly all children with dyslexia have challenges with accommodation. There may be problems with flexibility of accommodation. In such cases it may take several seconds, sometimes half a minute or more, to see clearly after changing focus from a short to a far distance and back. There may also be challenges with stability of accommodation. In such cases, the child is unable to keep a clear focus on the text.

If the focus is not stable, the text will become blurry or start to move. These problems usually become evident after the child has been reading for a while. Thus, reading becomes more challenging the longer the child reads. If the child needs to strain his eyes to see clearly, this may also cause headaches and irritated eyes. To compensate for poor stability of accommodation, the child may move the text back and forth to see it more clearly.

Besides insufficient practice of accommodation as a baby and a non-integrated STNR, accommodation may also be obstructed by stress. This is especially the case if the stress reflexes, like the Fear Paralysis reflex and the Moro Reflex, are retained.

The ciliary muscle inside the eye, which controls accommodation, is innervated by the parasympathetic nervous system and is therefore dependent on a calm and relaxed inner environment to function properly.

In stress, especially if the Fear Paralysis or Moro reflexes are triggered, the sympathetic nervous system will take command and obstruct the contraction of the ciliar muscle. When the ciliary muscle cannot contract accommodation is affected and the ability to see clearly at a close distance will be blocked.

Signs of accommodation problems

- Child gets a headache or irritated eyes when reading

- Child blinks excessively or rubs his eyes when reading

- Child complains that the text becomes blurry

- Child holds the book too close or moves the book or head closer

- Child tires soon when reading

- Reading comprehension deteriorates the longer reading is continued

- Child avoids reading or reads as little as possible

- Child makes careless errors when reading or copying from the board. Small words such as of, as and is or small beginnings and endings of words are misread while long words like hippopotamus are recognized. (7)

Saccadic eye movements

When we read, the eyes move in a rapid, irregular jerky motion as they change focus from one point to another along a line. This is called saccadic eye movements. An inexperienced reader has more and longer fixations than a practiced one. In addition, unpractised readers more often move backwards along the line than practiced ones. These movements are called regressions. The same is true for dyslectics.

The saccadic eye movements are initiated by the frontal eye field, an area which has important neural connections with the cerebellum.

Symptoms of poor saccadic eye movements:

- The child moves his head rather than his eyes from side to side when reading.

- Needs a finger to keep place when reading

- Skips or rereads sentences

- Loses the place when reading

- The text hops

Dyslectic children and adults with deficient saccadic eye movements need help to improve them in order to become good readers.

Primitive reflexes and fine motor skills

In reading and writing disability the Grasp reflex and the Babkin reflex are often active. These are reflexes of the hands and if they are not integrated there will be problems with fine motor skill and writing.

If the Grasp reflex is not integrated the child may have challenges with the pen grip and to automatize writing. These children may press the pen hard and usually have poor handwriting. An active Babkin reflex may also cause poor fine motor skill and bad handwriting but may also obstruct articulation. Many children with this reflex active have problems to articulate clearly, which may contribute to their phonological difficulties.

Rhythmic movement training

The rhythmic movements infants do before they learn to walk are necessary for the development of motor abilities, integration of primitive reflexes and development of postural reflexes. They are also a prerequisite for the development of spoken language, visual skills, emotions and executive functions.

Rhythmic Movement Training has been developed on the basis of the innate rhythmic movements that infants spontaneously make. The program includes rhythmic exercises that integrate primitive reflexes, develop articulation and phonological abilities, develop visual skills such as binocular vision, accommodation and eye movements.

The rhythmic exercises stimulate the cerebellum and speech areas in the left hemisphere. When these areas are stimulated by rhythmic exercises speech, articulation and phonological ability will improve.

By adding visual exercises to the rhythmic movements, which integrate the STNR and ATNR, accommodation and binocular vision will improve. Primitive reflexes can also be integrated by applying a slight and even pressure in the reflex position, so called isometric integration. Such exercises in combination with visual exercises are particularly effective for improving accommodation and binocular vision.

The rhythmic exercises also stimulate the development of the prefrontal cortex and improve reading comprehension and executive functions.

In summary, Rhythmic Movement Training will help children and adults with dyslexia to develop the abilities which are necessary in order to automatize reading.

Case studies:

Anna

Anna was twelve years when I first met her. She had been diagnosed with dyslexia. She had never been able to read more than one or two sentences because the text immediately started to jump around and become blurry, which made her totally exhausted.

She had challenges both with accommodation and binocular vision and several retained reflexes among others the STNR and ATNR.

She started doing the rhythmic exercises every day and an isometric exercise to integrate the ATNR looking at a point. When she did this exercise her eyes became tense and irritated and she developed double vision. After some time these symptoms disappeared and after a couple of months she could read one page before her visual symptoms reoccurred.

Then she got an isometric exercise to integrate the STNR looking at a point. Initially the point moved and became blurry during the exercise but after some time it stopped moving. She continued doing rhythmic exercises and isometric integration for the ATNR and STNR twice a week during the summer vacation.

When I met her again a few months after the summer vacation her reading had improved dramatically. She had no longer any difficulties to read and during the summer she had read three books without any problems.

Pelle

Pelle was eleven years when I first met him. He could not read more than a sentence in a book with big letters before losing his concentration. His eyes became tired and irritated, the text started to jump and he got a headache. He had poor handwriting.

Otherwise Pelle had no problems with attention and concentration. A few weeks after he started the Rhythmic Movement Training he was examined by a psychologist and got the diagnosis dyslexia.

Pelle had several retained reflexes, among others the ATNR, STNR, Moro/Fear Paralysis and Grasp reflexes.

He started to do rhythmic exercises every day and an isometric reflex integration for the ATNR three times a week. After two months he could read for an hour before he developed a headache.

Pelle continued the rhythmic exercises and started to do an isometric integration exercise for the STNR in order to improve his accommodation. Later he started to do exercises for the Fear Paralysis and Moro reflexes.

After seven months of training the ATNR, STNR, Moro & Fear Paralysis reflexes were integrated. His reading had improved considerably and he could read more and faster than before. He still had some problems with spelling and his handwriting had not improved.

He continued doing the rhythmic exercises and started to do exercises to improve the Grasp reflex to improve his handwriting

A year after he started Rhythmic Movement Training, Pelle loved reading and he could read several books a week.

He had started to borrow adult literature in the library and he also brought books to school which he read when he found the teacher boring. When criticized for that he said that he had no problems reading and listening to the teacher at the same time. His spelling was now almost faultless and he could write without problems with a considerably better handwriting.